My mother has been making umeboshi every year since I was very young. One day, after I got married and left my parents’ home, I wanted umeboshi and bought some at a store. I was disappointed with the taste of the store-bought umeboshi, though they looked so good and were rather pricey. The type on the market these days is not very salty or sour; it’s not what I think umeboshi should be. Since many people prefer a low-salt diet for health reasons, low-salt umeboshi has been more popular on the market. These, however, contain sweeteners and food coloring and I wonder whether they provide umeboshi’s original health benefits.

So I asked my mother to make her all-natural, homemade, sour and salty umeboshi. She has achieved a considerable reputation as an umeboshi-maker in her neighborhood. While I have been able to obtain good quality umeboshi without too much effort so far, my mother has been getting older and it is a physical burden for her to carry heavy loads of umeboshi ingredients home from the shops and to work on the pickling in standing or sitting positions. Therefore, I made up my mind to learn how to make good umeboshi directly from my mother, the umeboshi master.

It seems that many of you think making homemade umeboshi takes extra effort and time. Actually, it takes only a month to make umeboshi, from the beginning to the end of the rainy season. It’s an incredible, long life food you can make quickly and easily. Many people are too busy to make homemade preserved food these days; however, I would recommend you make homemade umeboshi because of the low cost, as those on the market are expensive and contain additives.

In order to make umeboshi, you will need: yellow ripe ume fruits, salt (approx.. 15% the total weight of the ume), shochu (Japanese distilled spirits, for disinfectant), a housing for pickling (an enameled or food grade plastic container), a drop lid, a weight, bunches of akajiso (purple perilla herbs), a zaru (draining basket), and a storage container.

In late June, during the rainy season, obtain ripe ume fruits. After rinsing the fruit, put them into a pickling container. Pour water into the container to soak them. Remove the ume and water from the container the following day and clean the container. Take out the stems of the ume one by one and put them into the shochu-sterilized container with salt (top-left image). Put the shochu-sterilized drop lid on the salted ume, then put the weight on the lid (top-middle image), close the outside lid and then place the container in a well-ventilated place. There will be plenty of moisture from the ume due to the osmotic water shift (top-right image). This sour and salty liquid is called umezu.

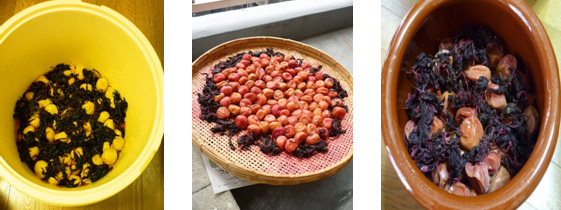

When you have an adequate amount of umezu, put akajiso into the pickle. Rinse akajiso leaves in water, and then rub the leaves with salt to remove harshness and rinse them well in water. Squeeze the water from the akajiso leaves and pour a small amount of umezu into the akajiso and rub the leaves a bit and squeeze them. Spread the prepared akajiso on the ume in the pickling container (top-left image), and put the drop lid, weight, and the outer lid back on. Allow the mixture to pickle until around late July, at the end of the rainy season. During the sunny days immediately following the rainy season, put the ume and squeezed akajiso on a zaru to dry outside during daylight hours for three days (top-middle image). This is umeboshi. Put the umeboshi and akajiso into a shochu- sterilized storage container with a small amount of coarse sugar and keep the container in a cool place (top-right image).

Umeboshi is used in many different ways besides consumption. For example, sardines cooked with umeboshi are tasty with no fishy odor so you can eat the fish whole. You can also use umezu, a byproduct of umeboshi pickling, to make nagaimo (Chinese yam) pickles (top-right image). The pale rose-colored yam pickles look elegant with a crisp texture. Making homemade pickles like these will be a benefit considering how expensive they are in stores.

It seems that umeboshi recipes vary slightly by area or household. The umeboshi that are pickled in a clean environment and firmly dried can be stored for several years even at room temperature. Now that I have learned the efficacy and how to make umeboshi, I plan to make the pickles every year and someday pass the recipe on to someone so that this traditional Japanese food does not decline.

Next, I will report on current umeboshi-related food trends.

Reported by Yukari Aoike, Sugahara Institute