Over the past 5 years the establishment of new international schools continues at a rapid rate (refer to the previous article “1. Sudden increase in international schools”). Why are Malaysian people becoming more interested in international school education recently? To understand this, it is necessary to look at the setting of the Malaysia education system today.

The education system in Malaysia is much more complicated than the largely mono-racial education system in Japan, and a lot of specific issues arise because Malaysia is a multiracial country.

Firstly, there are the language policies of the school system.

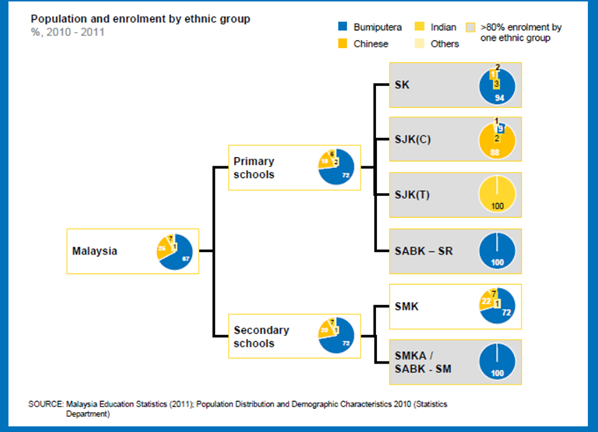

There are “national schools (SK)” and “national-type schools (SJK)” for primary schools. SK use Bahasa Malaysia, SJK (C) Chinese and SJK (T) Tamil. The Malaysian education system provides options for parents to create ethnically-homogeneous environments at the primary level (6 years).

However, it is important not to ignore the Bumiputera Policy aimed at improving the economic standing of the Bumiputera (the Malay race and other indigenous peoples) which represents over 60 percent of the population and receives preference in areas such as university admissions and civil-service jobs.

The secondary level consists of 3 lower years and 2 upper years, the SMK for Bahasa Malaysia, and the presence of a single secondary school format does create convergence.

To Japanese, the Malaysian education may seem somewhat old-fashioned. Similar to the traditional Japanese style of learning by rote, its emphasis is on national examination results at the end of primary, lower secondary, and upper secondary education (UPSR/PMR/SPM) and places are allocated to students according to scores.

It must be very hard for Chinese and Indian Malaysians to integrate into SMKs (the schools using Bahasa Malaysia), and the effects of the Bumiputera Policy continues throughout the education system to admittance into national universities and employment.

I suppose it would be less burdensome for non-Bumiputera to go to SK, (national schools using Bahasa Malaysia), however, the data shows that the great majority of non-Bumiputera choose to go to SJK(C) for Chinese and SJK(T) for Tamil through respect for the mother tongue or benefits in the future. Moreover, it’s surprising that there is an increasing number of Malay and Indian applicants going to SJK(C).

According to the data, 99% of primary level students go to public schools, of which 74% enroll in SK, 21% in SJK(C) and 3% in SJK(T).

The racial ratio in each school is:

SK (National School in Bahasa Malaysia): Bumiputera (Malay) 94%, Chinese 1%, Indian 3%

SJK(C) (National-type School in Chinese): Bumiputera (Malay) 9%, Chinese 88%, Indian 2%

SJK(T) (National-type School in Tamil): Indian 100%(Source:http://www.moe.gov.my/userfiles/file/PPP/Preliminary-Blueprint-Eng.pdf)

What about private education in Malaysia?

Approximately 3% or 145,000 of students aged 7 to 17 were enrolled in private schools (1% of total primary enrolments and 4% of total secondary enrolments) from the data for 2011. These schools are mainly categorized private schools that teach the national curriculum: local private schools, international schools, religious schools, and Independent Chinese schools.

Independent Chinese schools operate only at the secondary level and are very competitive among Chinese students. 46% of the 145,000 students in private schools today enroll in the 60 nationwide schools. The schools prepare students for a standardized examination known as the Unified Examination Certificate (in Year 6 of secondary school), although many schools also prepare their students for the SPM. The workload for students is said to be seriously intense. It’s not uncommon for Chinese families from the beginning to opt out of the Malaysian education system, seen as being disadvantageous for their children, and gear them towards overseas universities.

When I consider the Malaysian education system I feel that, despite being a multiracial country, it is a system characterized by inequality between different races and unfair conditions.

I asked my Chinese Malaysian friend how she felt when she couldn’t enter the national university because of its race quota. She said that of course she was frustrated, but her response about the situation wasn’t as strong as I had expected since she didn’t complain about the Bumiputera policy or show any anger about the different social standings of the various racial groups in Malaysia.

I don’t know the reality, but Chinese Malaysian are culturally different from Malay people and tend to be predominant economically, so it may be easier for them to accept this simply as a matter of being different. If the same situation of preferential treatment existed in Japan, there would be mounting tensions.

There have been racial riots in the past, but Malaysia is said to be peaceful internationally in comparison to other countries and the national character moderate. I think Malaysian people have wisdom about living with ethnically different people because of its long history.

Malaysia is a multiracial country and, as such, it has certain specific educational requirements. If economic problems can be resolved, it looks like the private education market with its international schools has the potential for growth.

Reported by Makiko Wada, Sugawara Institute