Oise Mairi, the First Group Tour by Japanese Common People

When the regime changed from the Emperor to samurai in Japan, Ise Jingu was worshiped as the supreme deity. In the medieval period, however, when Japan was in the midst of endless wars, the Shikinen Sengu ceremony ceased for a while. During that time, wars resulted in damage to the Jingu site and the Jingu went through hard times both physically and economically.

Then onshi, priests who managed religious services in the Jingu, rose to take action. In order to promote visits to Ise Jingu among ordinary people including peasants, onshi traveled all over the country, distributing the useful Jingu calendar to homes and actively engaging in missionary work.

During the Edo period, when the world became stable, the transportation network including the Go-kaido, the five major highways was constructed, making traveling easier. That was when group pilgrimages to Ise Jingu gained great popularity among peasants and townspeople. People called the tour “Oise-mairi.”

Oise-mairi, a.k.a., okage-mairi was more like worshiping and sightseeing than a pilgrimage. Here, onshi did a great job – their work of distributing calendars served as a trigger to the trend of okage-mairi. Onshi played an important role in people’s travel to the Jingu not only as priests but also as Japan’s first tour conductors. In this period, one out of six people went to worship at the Jingu every year, and there’s a song with lyrics like “…I want to go to Ise even once in my entire life…”

So 5 million people, one-sixth of Japan’s total population of 30 million at the time, traveled in groups every year. If the same thing had happened in China, the tour groups would have been regarded as a religious rebellion and executed. Traveling at that time was what you did at the risk of your life anywhere in the world. Therefore, people would travel with bodyguards. Under the circumstances, it must have been a miracle that it became the norm for people in Japan to make such unconstrained, risk-free trips to the Jingu. Considering the fact that at the time doing things in groups was a security risk, we should say that the security management of the Edo Shogunate was wonderful for its generosity.

People traveled on foot from every region of the country to Ise Jingu, and it took about 15 days from the town of Edo. It was really a long trip and naturally cost a lot of money. The trip was not what ordinary people could easily afford. So they establish a reserve fund system called “Ise-ko” in each community. Each member routinely paid a certain amount of money to the travel fund through which they covered the travel expenses for the party of representative members who would go to Ise. The representatives were chosen by lottery and the winners would go to worship the Jingu on behalf of the community.

The abovementioned funding system, called ko, effectively allowed poor people to fulfill their desires without borrowing money from a bank until the Showa period. The ko system worked when there was a mutual trust between persons involved, but it wouldn’t have worked if someone got money and ran off with it. Therefore, the system worked only because of the national characteristic of keeping promises.

During the Edo period, traveling was strictly restricted among peasants and townspeople; they were not allowed to go on long-distance trips without a travel permit. However, if the purpose of their trip was to worship at the Jingu, the permit was easily acquired and they could pass through the checkpoints. Even when townspeople went on the trip without telling their parents or their master, they were not punished at all if they got home with evidence such as talismans and souvenirs which proved they worshiped the Jingu and prayed for business success. Good times, don’t you think?

During their journey to Ise Jingu, they had a really good time. They fully enjoyed the tour.

Onshi, the priests and the most powerful tour conductors, were there for them just like tour guides. The onshi took the travelers sightseeing and taught them how to worship at the Jingu. The travelers were able to taste good sake and enjoyed feasts fit for a king, sleep on a soft futon, and have a great trip that was literally an once-in-a-lifetime experience. Of course onshi themselves gained a lot from the tours.

Thus, in the Edo period the Ise Jingu thrived.

As you can see, the lifestyle of Japanese people in the Edo period seemed loose and pleasant, and somewhat adventurous. According to records, women enjoyed the trip just as men did, so the status of women at the time may have been better than in the Meiji period. For those who lived on the road it was only natural to support travelers. It was common for the locals to provide travelers with a place to rest, as well as benches, tea, and sweets. Even today, there are many people who voluntarily support travelers. Like the phrase okage sama de, which means “thanks to you,” everyone in the Edo period knew that charity is an investment; if someone traveled and spent money, the money also traveled and turned the economy upward. We think this outlook shows that they valued a tenderhearted, win-win relationship beyond their ecological living.

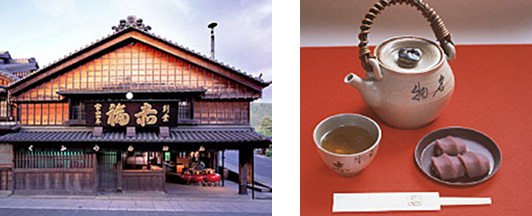

There is a shopping street called Okage Yokocho near Naiku of the Jingu. There are many restaurants and souvenir shops in the street, attractions for those who visit the Jingu.

Especially when we hear the words Ise Jingu, they remind us of a Japanese sweet cake, Akafuku. Akafuku is famous and sold nationwide but tasting Akafuku at the original store is especially good.

When you visit and worship the Jingu, we recommend that you come to Okage Yokocho.

Okage Yokocho (Mie Tourism Guide): http://tourismmiejapan.com/search/spot.php?act=dtl&id=36

Reported by Yukari Aoike and Akiko Sugahara, Sugahara Institute