“The best part of traveling is the moment when you unexpectedly come across something interesting.” When we say the above in Japanese, we often use the word “daigo-mi” to describe “the best part.” Daigo-mi literally means “taste of daigo,” but we don’t know what daigo tastes like and we wonder how it tastes.

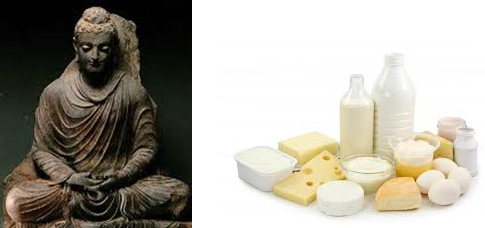

I checked the origin of the word daigo, and found that the word was mentioned in a Buddhist scripture called the Nirvana Sutra. According to the sutra, The Nirvana Sutra is the best of all the Buddhist texts just as “daigo” is the best of all the five flavors (gomi) in the processing of dairy products.

Regarding gomi (the five flavors), the sutra mentions that milk is processed like this:

nyu (milk) –> raku –> sei-so –> juku-so –> daigo

Therefore the last one, daigo, was supposed to be the best flavor, equivalent to the best Buddhist sutra and the highest-quality product made from milk.

Buddhism and dairy! What a surprising combination. Even more surprisingly, dairy products existed when Buddhism came to Japan from India through China and Korean peninsula. Was daigo something like butter, or more like cheese?

Buddhism was introduced to Japan about 1,500 years ago. On the other hand, milk products became popular among Japanese people after World War II. In the meantime, I don’t think the average person in Japan had ever tasted milk or cheese. If so, daigo may have been Japan’s oldest cheese.

By the way, when and how was cheese first made?

Cheese is made when you curdle milk in some way or another, solidifying it by draining the water. There are several theories about the origin of cheese and it is unknown which one is accurate, but it is said that cheese was first introduced to the world about 6,000 years ago.

Among dairy products, there are so many kinds of cheese made of different ingredients and by different processes. Like bread and wine, cheese was first made by chance, but there are three main cheese-making processes. These are to: 1) curdle milk by adding rennet, which contains enzymes; 2) curdle milk by adding an acid such as vinegar; and 3) simmer milk until it becomes solid.

Various kinds of cheese we have today originated in Europe, and most of them are manufactured by method no.1 (enzyme coagulation).

Well, how was daigo made?

According to the Nirvana Sutra, daigo was so delicious, and cured all sorts of diseases. In the Asuka period, a culture of milk products was introduced along with Buddhism. Regarding so, one of the introduced dairy products, whose quality level was just below daigo, the processing formula and the historical record that show it was used for a tribute to Emperors were found in Japan’s ancient documents such as Engishiki. So was a very rare and valuable processed food providing good nutrition that only people of the noble class were able to enjoy.

So was made by the abovementioned method no. 3 – simmering cow milk – until it became solid and matured. This is probably Japan’s oldest milk-based processed food. However, there’s no record mentioning that daigo was produced in Japan. Eventually daigo was not available in Japan. Later, the culture of eating milk products in ancient Japan passed away as aristocratic society came to an end.

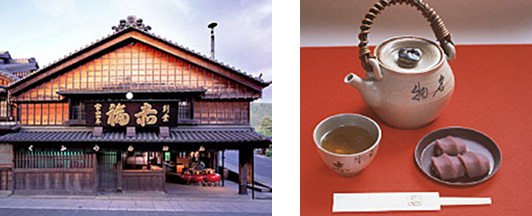

So, I was not able to taste daigo. However, you can taste so instead of daigo! A dairy farm at the south foot of Mt. Kaguyama, Nara pref., where the capital of the Asuka period was located nearby, succeeded in producing so based on the ancient recipe and put it on the market under the trade name “Asuka no So.” It is a natural food made only by milk, using no additives.

I got this so via the Internet. Asuka no So is a brownish square cake with a hard crust on the surface, obviously looking like an ancient cheese. You can taste its sweetness and rich flavor of milk. Yes, it should be cheese. This is a dairy product that only a small number of noble people were able to enjoy in the Asuka period about 1,300 years ago. Thanks to the word daigo-mi meaning “the best part,” I was able to savor the taste of the best part of Japan’s ancient past – its oldest dairy product , as revived in the present.

“Asuka no So” Milk Kobo Asuka’s website: http://www.asukamilk.com/so/index.html

Reported by Yukari Aoike, Sugahara Institute